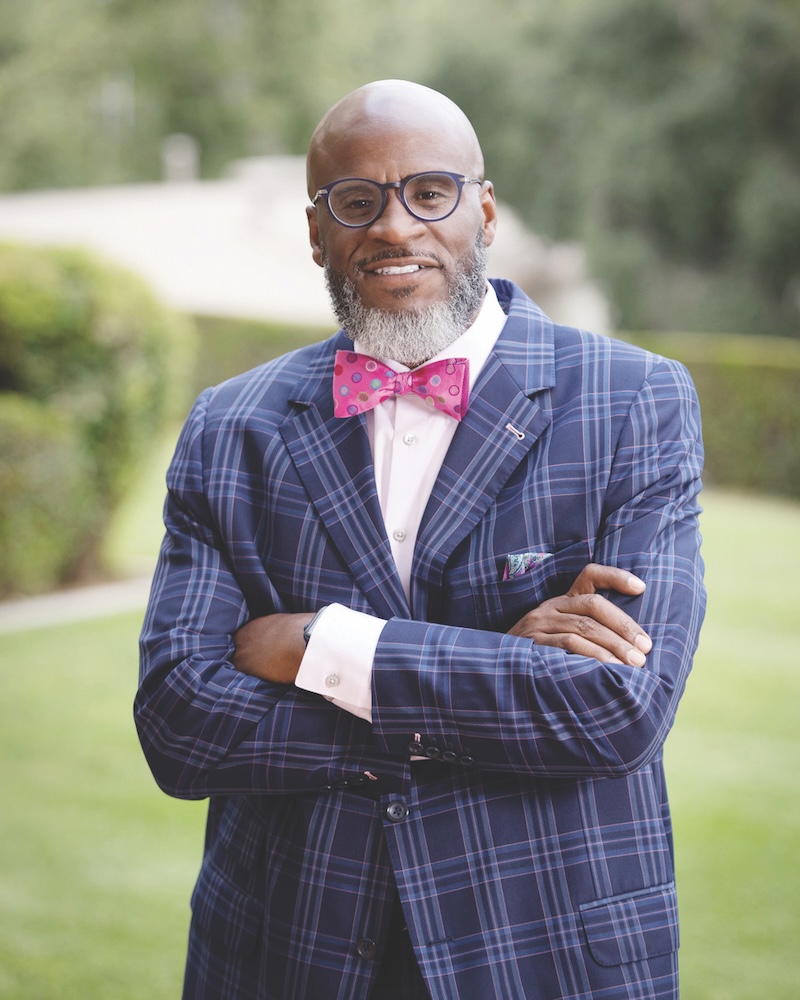

Pastor Samuel Casey: Radical Belonging

Pastor Samuel Casey is a prominent figure in community organizing and social justice in California. As the senior pastor and co-founder of the New Life Christian Church, he combines his faith with a passionate commitment to social change. Casey is also the founder and executive director of COPE (Congregations Organized for Prophetic Engagement), an organization dedicated to dismantling pipelines to mass incarceration and addressing issues such as healthcare, housing, and education equity.

With a calling to preach since age 13, Casey began his journey in ministry in the early 1990s. His work in community organizing started in 1999, leading to significant policy victories and collaborative efforts across California. Under his leadership, COPE has grown into a substantial organization that protects and revitalizes communities.

Casey’s approach intertwines grassroots activism with faith-based principles, focusing on empowering marginalized communities and promoting justice reform. His work has contributed to changes in school policies, reentry programs for formerly incarcerated individuals, and statewide initiatives addressing systemic inequalities.

Q: Can you tell us about your journey to becoming a pastor and community organizer?

Pastor Samuel Casey: I come from a family of faith, with several pastors in my lineage. I’ve known I was called to preach since I was 13. I’ve been preaching since then, around 1993-1994. In 1994, a gentleman named Reverend Gene Williams II, who became my mentor, joined our church in Watts, California. He had launched an organization called Regional Congregation and Neighborhood Organizations (RCNO), which was a collective of small to mid-sized Black churches from Los Angeles, San Diego, and the Inland Empire.

I went to a national training that he put on in 1996. The organizing work grabbed me early on. In 1997, Reverend Williams recruited me to become the organizer for the Inland Empire for the organization that would now be called COPE.

I started organizing on August 1, 1999, and organized our very first successful campaign in San Bernardino on October 1, 2000. From there, it’s been a whirlwind. COPE will be 25 years old next year, and we now have 13 staff members and our budget has grown significantly.

Q: Can you tell us more about COPE and its evolution?

A: COPE started as the Inland Empire chapter of RCNO, which at the time was probably the largest collaborative of small and mid-sized Black churches from here to San Diego, with Los Angeles as the real hub, and ultimately expanding to the Bay Area.

Since 1999, COPE has evolved as an organization. At one time, we were really a single-issue organization, focusing solely on mass incarceration or dismantling and disrupting any pipeline that led to mass incarceration. Initially, the focus was really on Black men. But it has evolved now to include women, children, and youth.

Our north star is still to dismantle any roads and disrupt any pipeline that leads to mass incarceration. Where it intersects now is healthcare, housing, civic engagement, education transformation, and justice transformation. There’s a seamless thread of leadership development in each one of those areas, led by grassroots leaders – those closest to the problem and the conditions in the community.

Q: Can you share some of COPE’s policy victories and their impact?

A: One of our very first policy victories in 2000 was AB 743, which mandated that individuals convicted of nonviolent, non-serious crimes could be placed on probation and required to get their GEDs or successfully complete some form of high school education. This was for those who didn’t have a GED or high school diploma, as a way to reduce their penalty and/or have their fines reduced and that charge removed from their record.

From there, we began to challenge not only the state but really the counties of Los Angeles, San Diego, and the Inland Empire to begin to focus on caring for the needs of those who have been formerly incarcerated. We pushed for the development of what was called the “Reentry Task Force” in San Bernardino and Riverside. It evolved into the “Public Health Reentry Task Force” to address communicable diseases and other needs of those who have been formerly incarcerated, once they are released.

These efforts led to the establishment of the San Bernardino County Reentry Collaborative, where all organizations involved in service delivery for formerly incarcerated individuals came together. While it’s not as strong as it used to be due to changes in laws like AB 109* and Prop 47**, it has had a significant impact on how resources are allocated and how the needs of formerly incarcerated individuals are addressed.

Q: How do you feel your work has had a ripple effect throughout California?

A: The work we’ve done, along with other organizations throughout the state, has literally changed the face of how we’re thinking about incarceration. We’ve been able to push for changes that have affected how schools work with school police departments. For example, Oakland has dismantled its school police department, and the L.A. Unified School District has reduced the resources it’s giving to school police.

Laws have been changed around willful defiance, clarifying its definition in school districts. Places like San Bernardino, Stockton, and Fontana have all been put on notice about their disproportionality in suspensions and expulsions. I believe this is the work that we, along with other organizations throughout the state of California, have impacted not only locally but regionally and ultimately statewide as we look at harmful policies and practices.

Q: How does your faith intersect with your work in social justice, particularly in addressing the racial disparities in the justice system?

A: I believe that Jesus, while on Earth, was the greatest community organizer and social activist that ever lived, and anyone who claims to be his follower must do likewise.

My faith has really built my conviction that I literally stand on the shoulders of not only Jesus Christ, but Medgar Evers, James Cs, Dr. King, Malcolm X, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and so many others who have come before me.

There are two specific texts that root me in this work. One is Micah 6:8, “What does the Lord require of you? But to do justice, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God.” The other is in Matthew 25, where Jesus talks about distinguishing between those who truly follow him and those who don’t, based on how they treat the marginalized – visiting those in prison, clothing the naked, feeding the hungry, housing the homeless.

I believe all of that is a work of justice biblically. God is a God of justice and will always be on the side of the oppressed, the marginalized, the widow, and the orphan – those who do not have access to the table of radical belonging. So anywhere that doesn’t exist, I believe there is a call on my life to participate in a process that widens the circle of human concern rather than constricting it.

Q: Can you discuss the California Black Freedom Fund (administered through Silicon Valley Community Foundation, this is a five-year, $100 million initiative that prioritizes investments in Black-led organizations confronting racism) and its impact since its establishment in 2020?

A: I believe the California Black Freedom Fund is not only accomplishing its goal, but it’s expanding the capacity of organizations like COPE and other Black-led and Black-empowering organizations throughout the state of California.

Here’s the rub, though: It shouldn’t have taken the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tamir Rice, and others for this fund to be established. We’ve been voicing our needs for years. While I’m proud that the Black Freedom Fund has built capacity and increased our reach, allowing our budgets to grow radically in a short period of time, there are challenges ahead.

Will Black remain the “new black”? Will Black issues still be of interest, especially in California where our population is declining? Will we still be considered separately, or will we be lumped into “people of color”? Will the resources still help us fight anti-Blackness, even when it comes from other people of color?

I believe it’s a success because when I look at organizations like COPE and what the Black Freedom Fund has helped us establish… it’s significant.

The Black Freedom Fund has increased capacity at a state level that trickles down to the regional level, which then helps those at a local level to affect change locally, regionally, and statewide. It’s a symbiotic relationship and a process that will continue to evolve with the right kinds of support.

Q: In a fractured society, you’ve mentioned that bringing the truth tends to get people to come to the table, even from opposing opinions. What truths have you found that get people talking and collaborating instead of fighting?

A: I have to give credit to a new friend and brother of mine, Reverend Ben McBride, who’s doing powerful work on othering and belonging. I believe that the only way collaboration can happen and be sustained is if we can come to the room without belittling one another. We need to thank one another and be courageous enough to have difficult conversations. We shouldn’t leave the room until we find radical belonging for everyone, even if it means that we must agree to disagree. But I commit myself to not inhibiting your thoughts, your insights, your being in the room and at the table.

It may be a lofty dream, but it’s crucial. I’ve had to confront my own biases. For instance, I didn’t realize how often I come to the room and forget that women show up in particular ways and must be honored. As a father of a transgender son, I’ve had to think about how, although I may theologically wrestle with it, I have no right to inhibit his access to a job, safety, healthcare, and all the things he needs.

Q: If you were hosting a small dinner party and inviting two or three other noted California philanthropists making an impact, who would you have over?

A: I would invite Dr. Bob Ross, the former president and CEO of The California Endowment. I would also invite Max Espinoza from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Q: Is there anything else you’d like us to know?

A: I have committed my life and my being to reflecting the greatest image of Christ on Earth, so that everyone I come in contact with, and the communities that I’ve engaged through the work of COPE, will find that we have left the world a better place than when we entered. I want to ensure that my living will not have been in vain.

*AB 109: Allows for current non-violent, non-serious, non-high-risk sex offenders, after their release, to be supervised at the local County level.

**Prop 47: Classified certain crimes as misdemeanors, changed resentencing laws and created the Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Fund to support rehabilitation programs and fund drug and mental health treatment.