Dispensing Arts to Heal Society

Artists, storytellers, teachers, and community leaders have long understood the power of art and story to transform individual lives, as well as society at large. From ancient times, and in cultures around the world, music, poetry, and dance were prescribed as medicine, and were viewed as fundamental to the healthy working of body, mind, and community.

For the last few generations in the United States, perhaps going back to the Russian launch of the Sputnik Rocket in 1957, public support of art and culture has faltered, replaced by an intense investment in science and technology. This bias has only accelerated in recent years, as the gravitational pull of high-tech and a religion of “productivity” has made it harder to justify the social value of the arts.

Ivy Ross, vice president of hardware design at Google, hopes to change all this with her new, best-selling book, Your Brain on Art: How the Arts Transform Us. Co-written with Susan Magsamen, founder and director of the International Arts + Mind Lab at Johns Hopkins University, Your Brain on Art demonstrates how the arts are neither a luxury, nor secondary to civilization, but “are essential to our very survival.”

Your Brain on Art synthesizes recent findings in the growing field of “neuroaesthetics,” in which the impact of culture on our brains is proven beyond a shadow of a doubt. The authors note that engaging with the arts for even a few minutes each day leads to a panoply of benefits, including “enhanced self-efficacy, coping, and emotional regulation,” as well as lowering our stress hormone response and enhancing immune function.

“The science proves that we made a mistake, by downplaying the value of art, something for which we are physiologically wired,” Ross explained in an interview. She recently returned from addressing a group of 500 California school superintendents at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, where she unpacked the physical and mental health benefits of art, and argued for the return of art teachers to the school curriculum.

As we stare down an epidemic of loneliness in this country, organizations around the country are dispensing “arts” as an efficient solution, buttressed by studies proving the link between play, creativity, and health. “The opposite of play is not work,” Ross reminds us. “It’s depression.”

Long a national leader in finding creative solutions to wicked social problems, the Bay Area is full of talented artists, organizational leaders, and funders who are looking to amplify the benefits of arts for individual and collective health.

Sekayi Edwards, a Berkeley-based psychotherapist, is gratified to learn that neurological studies now prove what he has long seen in his practice – the profound impact of the arts on patient health. Working with music, video games, and epic storytelling activities like Dungeons & Dragons, Edwards sees how the arts “speaks to us all in ways we are not fully aware of. When we have the opportunity to create art, whether it’s in therapy, or a class, or just meeting an artist, we become expansive, instead of contracting.”

The framework of art, he continued, reduces the effect of trauma and chronic stress, which “prevents the shut-off of the prefrontal cortex, and makes it much easier to communicate and connect with others.”

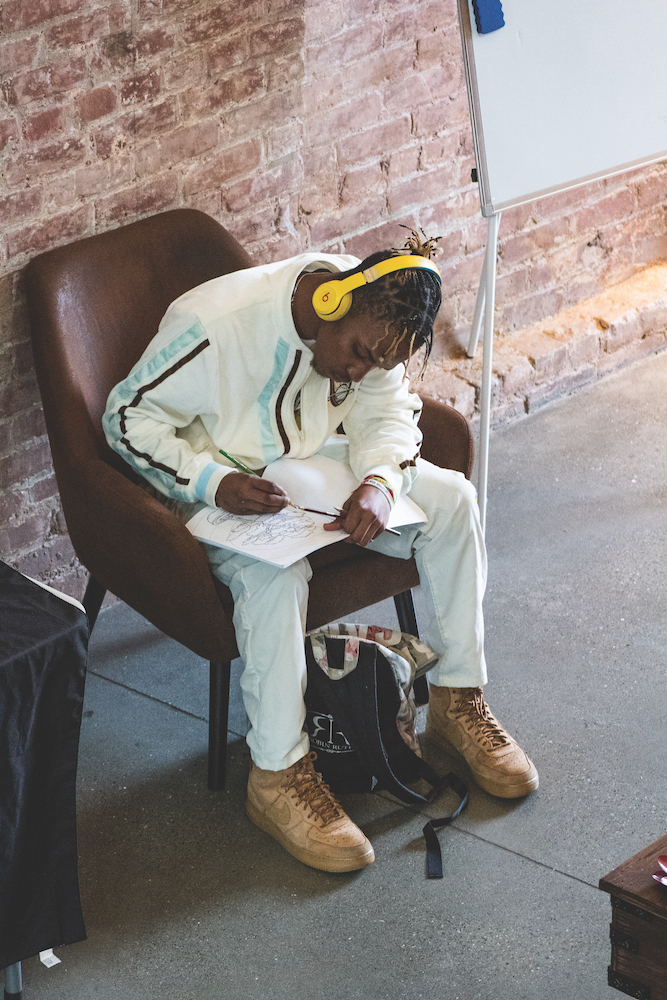

Through his practice, called Hidden Quest Therapy, Edwards has observed how the power of art transforms not just individuals, but groups as well. With a practice comprised mostly of teens and young men of color, he sees what happens when youth come together in a group process to co-create a narrative “that is neither stereotypical nor oppressive,” creating space for young people to “find their own voice, and a process that is bigger than just themselves.”

For 13 years, Cliff Mayotte ran the educational programs for Voice of Witness, a San Francisco-based oral history program that supports storytelling in traditionally marginalized communities from Oakland to Sudan. He has seen firsthand the transformation of individuals of all ages when they are offered the chance to tell their own story.

For youth, Mayotte said, “the skills of empathy, self-awareness, and collaboration that come from storytelling are transformational.” In one Voice of Witness study, students were interviewed seven years after a class, and a large number had shifted their professional trajectory to areas like nursing, journalism, and therapy.

These individual transformations, in other words, correlated with a sense of belonging and agency, “which inspired deeper community building and further empathy, in essence the qualities of good citizenship our country needs. These are the metrics that funders and policymakers want to see.”

Eric Pleschner is one of those funders. The long-time executive director of the Charles Becker Foundation, Pleschner has developed strong relationships with Voice of Witness, as well as local arts organizations like the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and First Exposures, which pairs youth with professional photographers. He describes the effect of these programs on participants and families impacted by social and economic inequality as “exponential,” going far beyond the results of one artistic project.

“We can come up with some numbers to associate with a program’s success,” he explained. “But we don’t really have a measurement system to capture the range of benefits derived from this work.”

Michelle “Mush” Lee, executive director of San Francisco’s legendary Youth Speaks, measures the impact one youth at a time. Her organization helps teen artists discover and amplify their voice, and by doing so creates community and effects social change. During the last few years, as she has watched a crisis of mental health unfold among the city’s youth, Lee tracked the compounding benefits of storytelling on Youth Speaks participants.

Lee offered the example of one student whose first public poetry focused on a neutral topic: what she ate for breakfast. But the process of safely telling stories about simple things prompted her to share more about her history and family. By overhearing herself speak, and feeling the love of a community of listeners, she began to make profound, positive changes in her personal life.

“The very process of telling stories in this way led her to new insights and new wisdom,” said Lee.

For Lulu Roberts, the founder of The Joy Culture Foundation in Palo Alto, the impact of the arts can be seen in how families read, dance, or even learn calligraphy together. Serving Chinese language communities in the South Bay, the Foundation encourages the qualities of intergenerational play and discovery. Like many others working with children and families, Roberts understands the value of neurological data to support the impact she sees firsthand.

“We know how important reading and visual stimulation is for young brains, and how those first five years are crucial in terms of parental and social investment,” she explained. Living in Silicon Valley, she worries about the “culture of striving” that is the dominant ethos, edging out a “culture of thriving” that encourages and celebrates play, empathy, and self-discovery.

For most of human history, marginalizing art and storytelling into silos would have made no sense. Their obvious social, spiritual, and biological benefits would have bound them deeply to a community’s health and identity. But in America, where market forces overwhelmingly act as our curator of creativity, it will take the commitment of a diverse group of leaders and funders to make plain what humans have known since the beginning – we are only as healthy as the stories we tell together.