Angel Martinez: Opportunity, Inclusion, and Giving Back

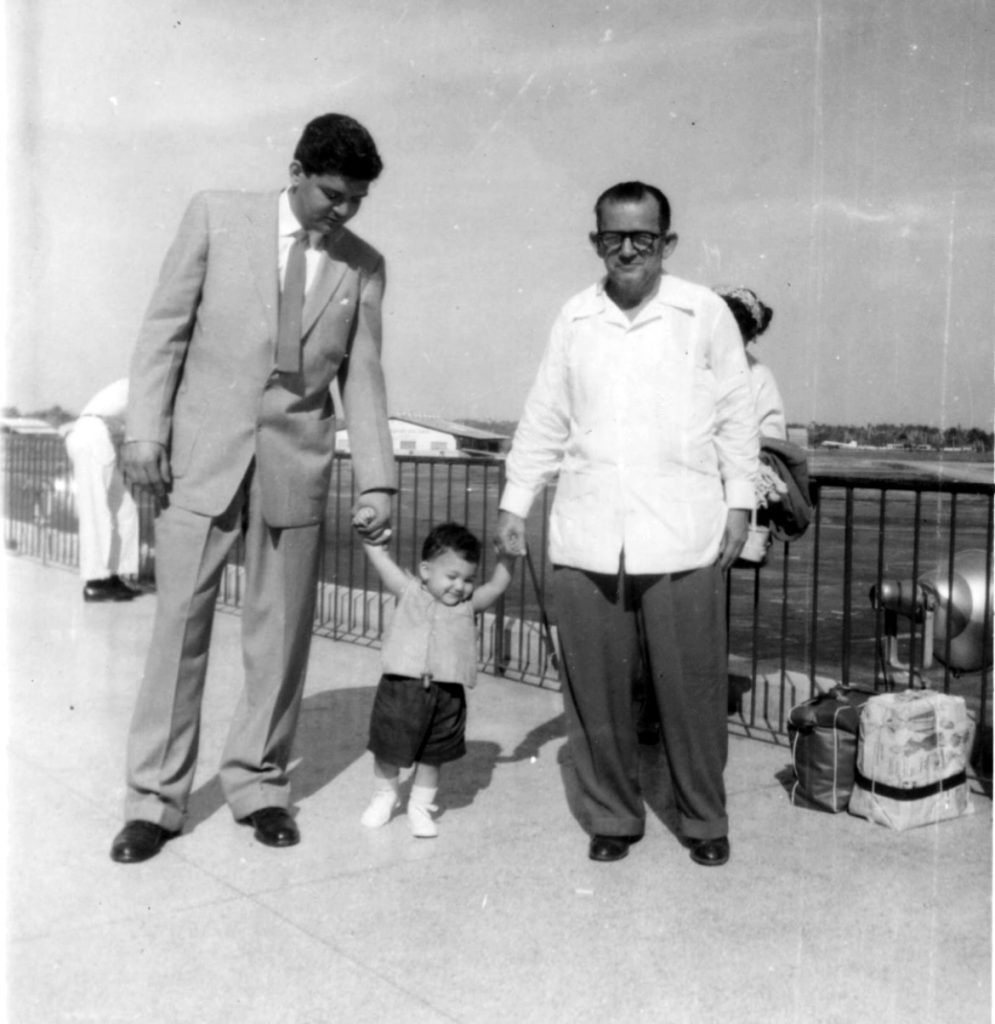

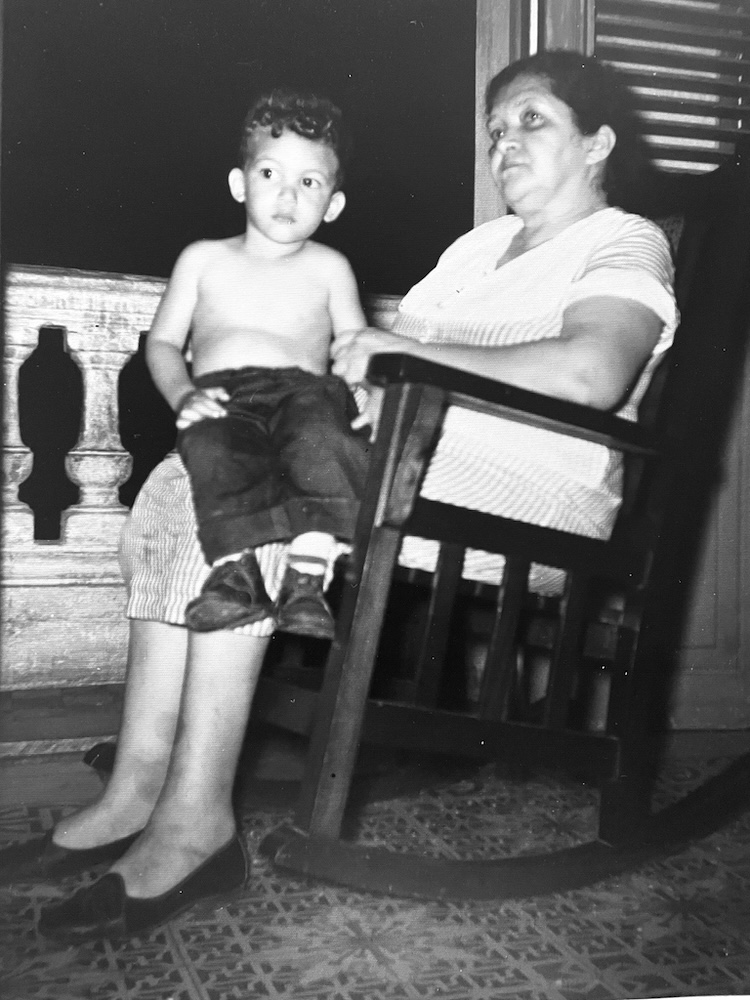

Born in Cuba and adopted at three months old, Angel Martinez immigrated at the age of three to the United States. His journey, from working-class immigrant to successful business leader is described by Angel as something of a Horatio Alger story; one that exemplifies the power of opportunity and belief.

A talented runner in high school, Martinez’s passion for athletics led him to the footwear industry where he played key roles in building iconic brands such as Reebok, where he spent 21 years, and Keen, a company he later founded. As CEO of Deckers Brands from 2005 until his retirement in 2016, Martinez grew the company from $200 million in revenue with 140 employees to $1.8 billion with 4,000 employees worldwide.

I was eager to speak with Martinez as a shining example of a successful leader who combined his corporate leadership with a passionate advocacy for corporate philanthropy, human rights, and creating opportunities for others. Among other things, Martinez was an executive producer of the Human Rights Now! World Tour in 1988 and has engaged with organizations like the Boys and Girls Club. Even in his limited (by choice) service on corporate boards like that of Korn Ferry, he continues to champion diversity, equity, and inclusion in the corporate world. His story is one of resilience, hard work, and a deep-seated belief in the power of collective genius and giving back to the community.

Q: Can you tell us a little about your journey to where you are today?

Angel Martinez: I was born in Cuba and I was adopted when I was three months old by my grandmother’s sister and her husband. My mother just split. My father worked for the railroad and was traveling five days, six days a week on trains. When I was three, my guardians immigrated to the United States because their kids had been immigrating since 1952. And so, we went to the Bronx in New York. I grew up in the Bronx until I was 13.

In 1967, we moved to Alameda, California … which was like moving to another planet. I actually thought the sidewalks would be made of wood and that people wore cowboy boots. I had a heavy Bronx accent at the time, and I was a little shit. I got in a few fights because kids wanted to pick on that weird kid from the Bronx who wore the pointy shoes.

One day I got called into the vice principal’s office, a guy named Renzo Quilici. He took me to a store called White Front and bought me a wardrobe. He bought me clothes that would allow me to fit in. I wonder today if any teacher would ever do that or take the time to do it. I never got in another fight in school again.

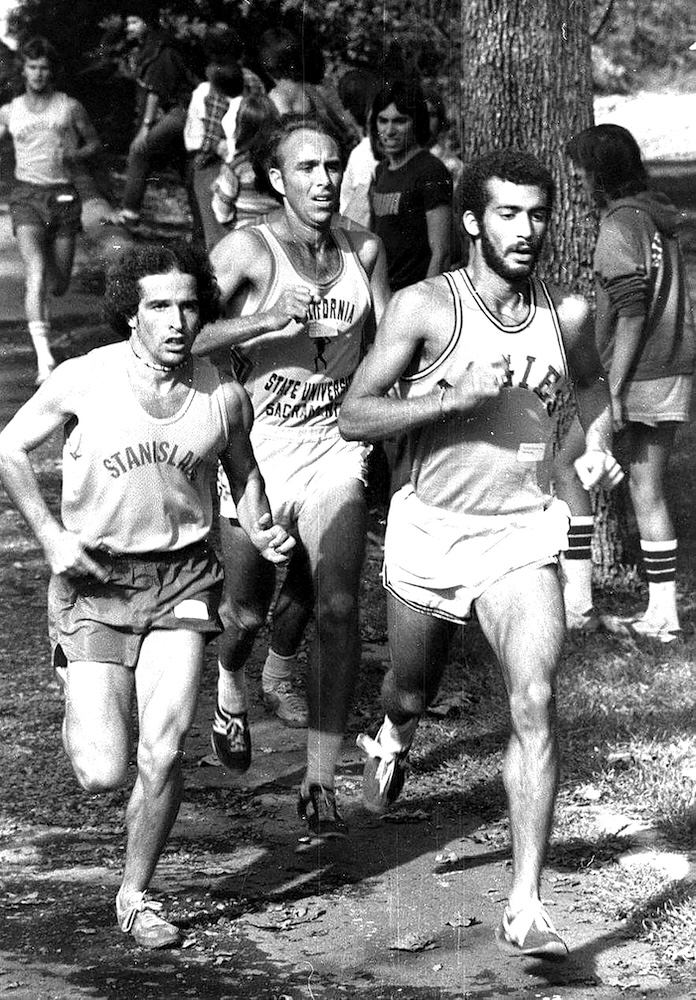

By the time I got to high school, another really important thing happened. I became a distance runner. For whatever reason, I was drawn to it. I was terrible at it. First year I was the slowest kid on the team. But by the time I graduated, I was one of the top runners in the state and broke the school record in the two mile and a mile and held it for 40 something years.

I had four-year scholarship offers at a bunch of schools, but [my guardian/my mom] had health issues and I didn’t want to go to college and be a flight away or a six-hour drive away, so I went to UC Davis, which was the best decision I ever made. I loved it there. Sophomore year I met my wife, Frankie, there. We’ve been married for 45 years now.

Q: As an immigrant child, who was deeply impacted by being separated from your family, what do you think gave you the strength to endure that?

A: My guardian was born in 1901. So, between…1912 and 1918 he went to live with his older brother in Syracuse, New York. Because in those days in Cuba, if there was any possible way that you could get your kid to America for an American education, you did it.

He was committed to the idea that America was a place of opportunity and that there was nothing you couldn’t do if you just got here. So, that was deeply embedded in my belief system. That’s why all four of his kids immigrated.

Belief is a very important thing for a kid, that people believe in you and that you believe in yourself. That’s the thing about running that was so important for me, because you have to learn to believe in yourself if you’re going to be a successful runner or any athlete. But running is one of those things that’s very hard to do at a certain level when every day your body’s telling you, “Don’t do that to me.”

It was an immigrant mindset that you’re on the trapeze without a net. My guardian was disabled, so we relied on New York City public welfare, aid to families with dependent children, and food stamps. I was just a kid.

Q: Eventually you become the CEO of Deckers, which under your leadership had a very strong corporate philanthropy culture. Why?

A: Because if we didn’t do that, who was going to do that? Success, on that scale, has to breed success. Opportunity, on that scale, has to breed opportunity. Otherwise, you’re failing. It’s not about the money. None of this has ever been about the money for me. It’s about opportunity. It’s about creating as much opportunity as I can for as many people as I can, and challenging them to go for it. And if they don’t want to, that’s fine. You can leave. I was intolerant of people who didn’t want to put in the work or do what they should be doing to manifest the opportunity they had.

That was embedded in the Deckers culture, I think. When I started there, we had 140 employees and we were doing about $200 million in revenue. And when I left, we were at $1.8 billion and 4,000 employees around the world. Everyone pursued opportunities. There were opportunities created for tens of thousands of families.

At Reebok, too. At Keen, too, which is another brand that I started in the interim phase between Reebok and Deckers. That’s what it’s about. That’s why when Kamala Harris talks about an opportunity economy, it’s exactly what I’ve been talking about for my whole life. And if you create opportunity, and if you’re successful, part of your contribution is to spread that, to seed that, to create in people the idea that it’s not all about you. There are people out there who are just as smart as you are, just as capable in every way, maybe more hardworking, whatever, they just didn’t get the opportunities you got.

Q: Do you think that corporations, generally speaking, should more strongly prioritize philanthropy?

A: Of course. It’s all about greed now. It’s shocking that companies of the size that these companies are, that we still have hunger in the United States. It’s shocking that we still have kids sleeping in cars. It’s shocking that we’ve got so many billionaires in this country. Holy shit, how much money do you actually need? I mean, come on. Really. It’s insane. And yet, we have so many issues and problems that could be solved by just a fraction of their money, just a little bit more appropriate taxation. And instead, we defund schools and we restrict money for all kinds of important things that could make this a better country and could build a foundation of strength.

That, really, is at the core of what America’s about, the middle class. It’s true. It’s built America. And it isn’t just the middle class. It was the “lower class,” the immigrant class that built America as much as anything else did. The reason there were bankers making all that money, the reason there were miners, the reason that the oligarchs, as they were in the turn of the 20th century, existed, was on the backs of immigrants.

So, in my opinion, Deckers needed to be an important part of the community because it needed to demonstrate to other companies that it’s good for business to give back. The right kind of employees want to work for a company that wants to give back. Selfishness has no place there.

A company succeeds because people pull together. They pull together on one idea, they commit to it and they make it happen. And then, you create what I call a collective genius. And you actually learn to throttle that and encourage that. And suddenly unbelievable ideas start popping up all over the place.

Q: What causes are the closest to your heart?

A: Kids, opportunities for kids. What my teacher did for me in buying me a wardrobe, a couple pairs of jeans, a few shirts, and some sneakers. That’s why I’m involved with the Boys and Girls Club. When I was at Deckers, we made sure we were focused on that. When I was at Reebok, we were focused on human rights. That was a big issue. I was executive producer of the Human Rights Now! World Tour in 1988 with Amnesty International. That was Sting, Peter Gabriel, Bruce Springsteen, Tracy Chapman. Seventeen concerts on five continents over a month and a half period. Crazy, crazy thing. But we did it in conjunction with Amnesty International to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. And that’s when I discovered that most countries violate everything they signed up for when they signed the Declaration of Human Rights, including the United States.

Human rights violations exist everywhere in the world. And until we all learn that we’re all in the same boat here, we’re going to keep confronting these problems. The selfishness at the core of the political argument is incredibly destructive. And people don’t seem to understand that it’s just a path to failure. Everything is a zero-sum game. I can’t see you have something because it takes something away from me, instead of, why don’t we all just create something we can all benefit from? That’s the only way we’ve ever moved forward as humans.

Q: Can you elaborate on what inclusion looks like to you?

A: Well, first of all, if you close your eyes, say you were blind and you couldn’t see what the biases are out there, you couldn’t see a person’s skin color, you couldn’t see whether they had a handicap, you couldn’t see anything. All you could do was hear them. Your worldview would be totally different, wouldn’t it? The core of inclusion is this idea that you judge a person by who they are, the things that are important to them, what they value, that’s the important thing.

Inclusion is also the understanding that collective genius is a very powerful thing. Why would I, as a CEO of a company, restrict the quality of ideas that can come into this company? Why would I ever do that? I don’t care where the ideas come from. Best idea wins. And the people who want to work hard to make it happen.

Inclusion is, beyond inclusion of race, it’s inclusion of ethical standards. It’s inclusion of world views grounded on sets of ethical principles. As long as we’re all focused on the greater good, we succeed. I think in the end, when companies or societies do that, they win, and when they don’t, they struggle.

Q: Can you talk about the importance of small contributions in philanthropy?

A: It’s funny because when I was a kid, and I mentioned my teacher, Mr. Quilici. But in the Bronx, there was an organization that came into the neighborhood and they were recruiting kids to go to a camp, a camp called Camp Brookhaven. The cost was $2.50 for a week of camp. It was to pay for the gasoline to get the kids to and from the camp.

And I’d never been in an environment where there was a lake or there were trees or any of that stuff. I’d never eaten pancakes. I’d never done any of that stuff. Never really seen fireflies like that. The Bronx has trees, but they’re sequestered. And that was this organization, and we had Bible study every day for half an hour and learned all the gospel songs. But that really wasn’t what it was about. It was actual, true Christian charity. So, I was able to go twice to that camp. And that was a huge thing for me.

In the end, I guess a very small amount of money made a big difference to a lot of kids. What is perceived about philanthropy is that you’ve got to be able to write the big checks in order for it to really be philanthropy, which is nonsense, actually. Look at what’s happening in the elections with people writing $50 checks times 20 million. If we want to solve a problem, let’s understand that it’s a collective issue and that the small checks matter as much as the big checks.

And what’s unfortunate is that too many people focus on the big donors who write the big checks. And there’s a ton of people who, if you just tell them what it’s all about, tell them the difference they can make and the importance of it, they’ll give you 50 bucks or whatever, or give you their work on the behalf of the organization.

So, I think that’s one of the things we’ve got to get straight, is that philanthropy is about caring about the condition of other people and the path they may have to help you improve the world. I’d like to see a re-shift in how we think about philanthropy that way. Everyone should participate in philanthropy in one way or another.

Q: Any final thoughts on wealth, opportunity, and giving back?

A: In a sense, the perception of wealth and all of the things that it brings with it is intended to really be a barrier in so many ways. It’s intended to keep you from doing things. It’s intended to keep you from aspiring to things. It’s intended to keep you from participating in things because you’re not wealthy or because I can’t afford that, or I don’t belong there.

We must, as a culture, understand that the people do matter… And that when it comes to philanthropy, that five bucks is a lot of money to somebody who doesn’t have five bucks. And if someone makes $200 a week and they’re giving you $50, that’s a lot. That really matters.