Nichole Pettway: From Addiction to Advocacy

Nichole Pettway is a testament to the power of resilience and transformation. Once caught in the grip of addiction and incarceration, she has emerged as an accomplished scholar and a compassionate, dedicated advocate for those facing similar challenges. Today, Pettway serves as the program manager of social medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center, where she connects patients with resources beyond their immediate medical needs.

Pettway’s journey from addiction to advocacy is marked by determination and a commitment to education. She earned her GED, followed by degrees from City College of San Francisco and University of Phoenix. She holds a clinical master’s degree as a marriage and family child therapist and recently qualified for a doctorate in humanities.

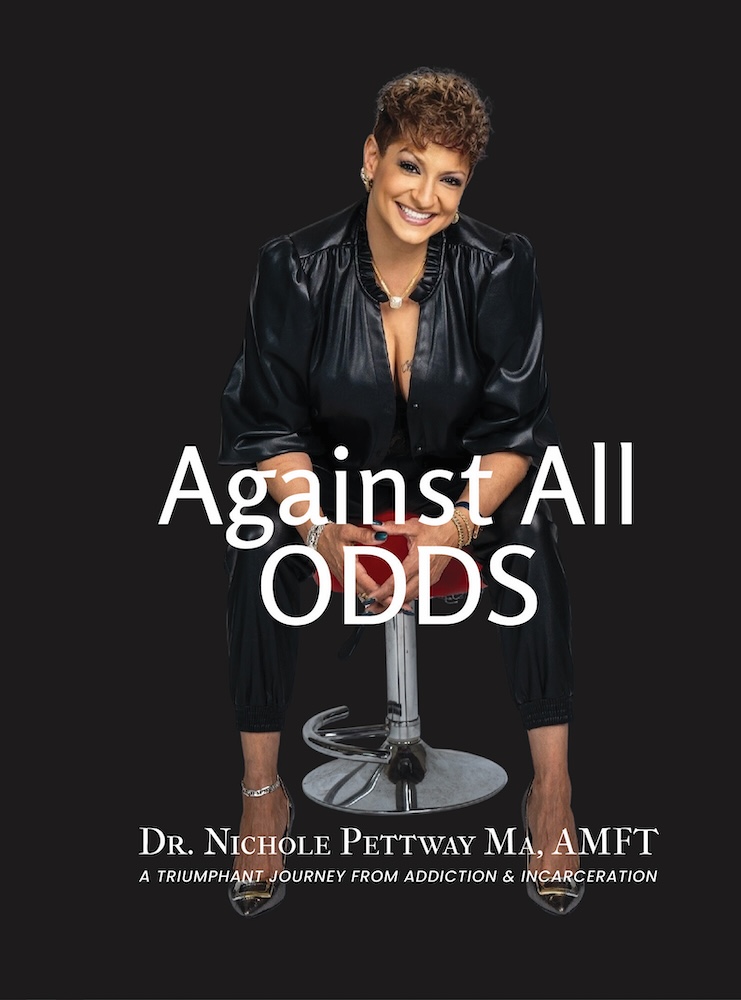

Driven by her experiences, Pettway founded the Building Bridges Foundation, which supports formerly incarcerated individuals in their reintegration into society. She is also a published author, having released her memoir Against All Odds: A Triumphant Journey from Addiction and Incarceration in June 2023.

Pettway’s work extends beyond her professional roles. She is a frequent speaker at recovery associations and reentry forums, sharing her story to inspire others and advocate for change in the criminal justice and addiction treatment systems.

Q: Can you share some of your remarkable history with us?

Nichole Pettway: I feel like I owe a lot of debt to San Francisco. I came here from Massachusetts in 1982, and by 1986, in this very hospital, I gave birth to my first child who was addicted to crack cocaine. I had never gone to high school and got caught up in the whirlwind of the crack epidemic. I was in and out of jails and institutions. I went to prison the first time in 1991 and got out in 1993. I was out for maybe 30 days, enough time to get pregnant again with my third child, whom I gave birth to in Chowchilla State Prison.

When I got out, I vowed to do something different with my life and went into a treatment program. I did really great for a good period of time, but I got complacent in my recovery and relapsed in 2003, winding up back in prison in 2006. I didn’t have any education and had lost everything.

Ninety days into treatment, I decided to go back to school and get a GED. I was embraced by the atmosphere of education, like I was embraced by the atmosphere of recovery. I went to John Adams Community College, then to City College from 2009 to 2013. I transferred to University of Phoenix where I completed a bachelor’s degree in business management. I continued on and completed a clinical master’s degree as a marriage and family child therapist. This year, on June 1, I qualified for a doctorate degree in humanities.

Q: How does your history inform both what you do in your career and your philanthropy?

A: In the emergency department, we work with patients whose chronicity of social issues and acuity of medical issues is low, but their social issues are high. We try to avert admitting patients into the hospital whose issues can be solved without admission, coming from a humanistic aspect. We provide support like clothes, hygiene kits, and help with shelter referrals. We also help patients get assessed for housing, assist with food insecurity, and connect them with benefits like CalFresh.

In my philanthropy, I speak at many different forums, recovery associations, and on stages across the United States. I focus on the importance of being there for folks who are being released from prison or jails, looking to empower certain communities with the resources it takes to reach the population. When you get out, you’ve got $200 “gate money,” and if you have no aspirations, you’re going to continue to go around in circles. San Francisco is pioneering in providing reentry services and assistance with reintegrating back into the community, and I want to be a part of that solution.

Q: What made you start the Building Bridges Foundation?

A: Sometimes it can feel like being on an island by yourself. Even though there are many people around you experiencing the same thing, having someone to help you create the bridge to the other side is crucial. I feel it’s incumbent upon me because there were so many people who were there for me, who “loved on me” until I learned to like myself.

I am a survivor of child molestation, and I started out in the sex industry, making it okay to participate in that type of behavior. Being there for another person who is in need, someone who just needs a “mustard seed of faith” and someone to help water and nurture that seed – I think it’s my responsibility to help someone in that way.

Q: What does your nonprofit, Building Bridges Foundation, focus on?

A: It is for formerly incarcerated individuals or pre-release individuals who really, from day one, what do you do when you get out and you’ve got no place to go, you’ve got $200 “gate money,” and what you know how to do would only lead you back to the same position that you’re in? And so I want to be that person that gives that information to someone who may feel alone and feel that they’ve burned so many bridges that there aren’t any bridges left to build. So I started Building Bridges Foundation.

Q: How can philanthropy be harnessed to help those who need a helping hand in finding their

full potential?

A: It’s about creating community, creating a safe space, and creating an atmosphere that’s welcoming. There’s nothing that you could tell me that would make me look at you any differently than another human being reaching out for help. I have been there, I have done that, and I have participated in things I am not proud of. But what I do know is that those were character-building experiences for me.

When I started to learn from the blessings in the lessons, when I started to really see that this didn’t happen by mistake – I am here as a testament of the resilience it takes for a person to succeed. But I can tell you that I didn’t do it alone. I know that I can do much more today, together with community, than I can do by myself.

Q: You’ve often quoted Mahatma Gandhi’s “Be the change you want to see in the world” as your mantra. How can the Bay Area follow suit and be the change?

A: It’s about leading by example, doing the next right thing for the next right reason, even when no one is looking, and developing personal integrity and an ethical standard for yourself. It shows in our community when we have a group of people that believe wholeheartedly that change is possible and know that it’s possible because they’ve changed themselves.

When you show self-love, it emanates, and other people want to be like you. There are so many people that lead by example in San Francisco, for me in my community. They say in Narcotics Anonymous, “The wider your base, the higher your sense of freedom.” Being around people who have been where you’ve been is powerful, but that’s not to say someone who hasn’t been where you’ve been couldn’t help you. It takes someone to start trusting the process for that to happen.

Q: What are the other most pressing social issues in San Francisco and the Bay Area?

A: Mental health is a significant issue. At one point in my life, I was more comfortable in a prison cell than I was on the street because the street was my prison. In prison, I went to bed at a certain time, got up in the morning, ate, brushed my teeth. When you’re on the streets, those skills aren’t practiced. Our lives get dwindled down to an animalistic level, and a lot of that has to do with mental health.

Substance use and homelessness are also major issues. There’s also a lot of women who are being trafficked, and young women getting caught up in selling drugs, holding packages or guns, taking cases. For me, it’s about self-esteem and self-worth, and how we embrace our communities and let them know that it’s okay to heal.

Q: Can you talk about how taking classes at the California Institute of Integral Studies affected your educational journey?

A: The support I received from my cohort was incredible. They stood up for me when I wasn’t able to continue with them in the integrative seminar [due to personal circumstances], and their advocacy led to changes in how I was treated by some of the faculty.

Despite the challenges, the educational experience overall has been the best for me. There were individuals like Rachel Bryant in the diversity and inclusion department who went above and beyond to support me. My cohort provided invaluable support, helping me with study sessions and paper writing. Their camaraderie and support were crucial to my success in the program.

Q: This past June, you published your memoir called Against All Odds: A Triumphant Journey from Addiction and Incarceration. What prompted you to write the memoir and what do you hope readers take away from it?

A: I’ve been writing my story for years, but the passing of my father last year, who was my last surviving parent, pushed me into action. I dipped into a bit of depression after his death, but I used the tools I would’ve suggested to anyone else – I called my sponsor, did 90 meetings in 90 days, even with 14 years clean, because I went back to basics.

This experience inspired me to write my book, open my business, and push myself further. I wanted to make sure that I wasn’t in the victim role in my voice. I wanted to let the reader know that every experience I had was character building, and that I stand here today as a victor. My book is for the person sitting in a prison cell feeling hopeless and helpless, feeling like suicide is the first option.

I wanted the book to be about coming out of the muck and mire of the disease of addiction and how it manifests itself in your life in many different ways. “Using” is just a symptom. It’s another way for me to reach out into the community and help lift others up.

Q: You work full-time, you’re a mother, a grandmother, you run a nonprofit, you mentor, you’re on the lecture circuit. How do you manage to do it all?

A: I joke that I have Energizer Bunny batteries in my back. But it’s also important to note that I have additional responsibilities. My second child was born with Sturge-Weber syndrome and is legally blind. After 33 years, I now have custody of her. I’m also raising a three-year-old grandchild whose mother abandoned her.

It’s challenging, but I’m driven by the desire to make a difference and to use my experiences to help others. Every challenge I’ve faced has made me stronger and more determined to create positive change in my community.